Jim DiEugenio’s

excellent and very important “How CBS News Aided the JFK Cover-up” – April 22,

2016 for Consortium News

https://consortiumnews.com/2016/04/22/how-cbs-news-aided-the-jfk-cover-up/

How CBS News Aided the JFK

Cover-up

April 22, 2016

Special Report: With the

Warren Report on JFK’s assassination under attack in the mid-1960s, there was a

chance to correct the errors and reassess the findings, but CBS News intervened

to silence the critics, reports James DiEugenio.

By James DiEugenio

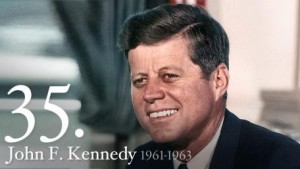

In the mid-1960s, amid

growing skepticism about the Warren Commission’s lone-gunman findings on John

F. Kennedy’s assassination, there was a struggle inside CBS News about whether

to allow the critics a fair public hearing at the then-dominant news network.

Some CBS producers pushed for a debate between believers and doubters and one

even submitted a proposal to put the Warren Report “on trial,” according to

internal CBS documents.

But CBS executives, who

were staunch supporters of the Warren findings and had personal ties to some

commission members, spiked those plans and instead insisted on presenting a

defense of the lone-gunman theory while dismissing doubts as baseless

conspiracy theories, the documents show.

Though it may be hard to remember – amid today’s

proliferation of cable channels and Internet sites – CBS, along with NBC and

ABC, wielded powerful control over what the American people got to see, hear

and take seriously in the 1960s. By slapping down any criticism of the Warren Commission,

CBS executives effectively prevented the case surrounding the 1963

assassination of President Kennedy from ever receiving the full airing that it

deserved.

Beyond that historical significance, the internal

documents – compiled by onetime CBS News assistant producer Roger Feinman – show how a major mainstream news organization

green-lights one approach to presenting sensitive national security news while

blocking another. The documents also shed light on how senior news executives,

who have bought into one interpretation of the facts, are highly resistant to

revisit the evidence.

Buying In

CBS News jumped onboard the blue-ribbon Warren

Commission’s findings as soon as they were released on Sept. 27, 1964, just

over 10 months after President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on

Nov. 22, 1963. In a special report, CBS and its anchor Walter Cronkite

preempted regular programming and, with the assistance of reporter Dan Rather,

devoted two commercial-free hours to endorsing the main tenets of that report.

However, despite Cronkite

and Rather giving the Warren Report their public embrace, other people, who

were not in the employ of the mainstream media, examined critically the report

and the accompanying 26 volumes. Some of these citizens were lawyers and others were professors, the

likes of Vincent Salandria and Richard Popkin. They came to the

conclusion that CBS had been less than rigorous in its examination.

By 1967, the analyses challenging the Warren Report’s

conclusions had become widespread,

including popular books by Edward Epstein, Mark Lane, Sylvia Meagher and Josiah

Thompson. Thompson’s book, Six Seconds in Dallas, was excerpted and placed on

the cover of the wide-circulation magazine Saturday Evening Post. Lane was

appearing on talk shows. Prosecutor Jim Garrison had announced a reopening of

the JFK case in New Orleans. The

dam was threatening to break.

The doubts about the

Warren Report had even spread into the ranks at CBS News, where correspondent

Daniel Schorr and Washington Bureau chief Bill Small recommended a fair and

critical look at the report’s methodology and findings. Top prime-time producer

Les Midgley later joined the effort.

CBS News vice president Gordon Manning sent the proposal

on to CBS News president Richard Salant in August 1966, but it was declined.

Manning tried again in October, suggesting an open debate between the critics

of the Warren Report and former Commission counsels, moderated by a law school dean or the president of

the American Bar Association. The idea was to give the two sides a chance to

make their best points before the viewing public.

Zapruder Evidence

One month after Manning’s debate proposal, Life Magazine

published a front-page story in which the Warren Commission’s verdict was questioned by photographic evidence from the

Zapruder film (which the magazine owned). Life also interviewed Texas Gov. John

Connally who disagreed that he and Kennedy had been hit by the same shot, a

claim that undercut the “single bullet theory” at the heart of the Warren

Report.

A frame from the Zapruder

film capturing the first shot that struck President John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22,

1963.

Without the assertion that

a single bullet inflicted multiple wounds on Kennedy and Connally, who was

riding in front of the President, the commission’s verdict collapses. The magazine story ended with a

call to reopen the case. Indeed, Life had put together a small journalistic

team to do its own internal investigation.

A few days after this

issue appeared, Manning again pressed for a CBS special. This time he suggested

the title “The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald,” with a panel of law school deans

reviewing the evidence against Oswald in a mock trial, including evidence that

the Warren Commission had not included. In other words, there would be a chance

for American “jurors” to weigh the evidence that might have been presented

against Oswald if he had lived and to make a judgment on his guilt. Again, this

approach offered the potential for a reasonably balanced examination of the

Kennedy assassination.

At this point, Manning was

joined by producer Midgley, who had produced the two-hour 1964 CBS special.

Midgley’s suggestion differed from Manning’s in that he wanted to title the

show “The Warren Report on Trial.” Midgley suggested a three-night, three-hour

series with one night given over to the commission defenders, one night

including all the witnesses that the commission overlooked or discounted, and the

last night including a verdict produced by legal experts. But the title itself suggested a

level of skepticism that had not been part of the earlier proposals.

The Higher-ups Intervene

However, then CBS senior

executives began to intervene. On Dec. 1, 1966, Salant wrote a memo to John

Schneider, president of CBS Broadcast Group, telling him that he might refer

the proposal to the CBS

News Executive Committee (CNEC). According to information that a former CBS

assistant producer Roger Feinman obtained during a legal hearing against CBS,

plus secondary sources, CNEC was a secretive group that was created in the wake

of Edward R. Murrow’s departure from CBS.

Murrow was a true

investigative reporter who became famous through his reports on Sen. Joe

McCarthy’s abuses and the mistreatment of migrant farm workers. The upper management at CBS did

not like the controversies that these reports generated among influential

segments of the American power structure. There was a perceived need to

tamp down on such wide-ranging and independent-minded investigations. After

all, the CBS executives were part of that power structure.

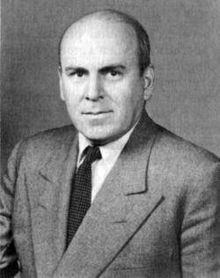

CBS News president Salant

epitomized that blurring of high-level corporate journalism and America’s

ruling class. Salant had gone to Exeter Academy, Harvard, and then Harvard Law

School. He was handpicked

from the network’s Manhattan legal firm by CBS President Frank Stanton to join

his management team.

CBS News president Richard

Salant

During World War II, Stanton had worked in the Office of

War Information, the psychological warfare branch. In the 1950s, President Dwight Eisenhower had

appointed Stanton to a small committee to organize how the United States would

survive a nuclear attack. From

1961-67, Stanton was chairman of Rand Corporation, a CIA-associated think tank.

The other two members of CNEC were Sig Mickelson, who had

preceded Salant as CBS News president and then became a director of Time-Life

Broadcasting, and CBS founder Bill Paley, who had also served in the World War

II psy-war branch of the Office of War

Information and – after the war – let CIA Director Allen Dulles have the spy

agency informally debrief CBS overseas correspondents.

When Salant turned the

Warren Commission issue over to CNEC, the prospects for any objective or

skeptical treatment of the JFK case faded. “The establishment of CNEC

effectively curtailed the news division’s independence,” Feinman later wrote

about his discoveries.

Further, Salant had no journalistic experience and was in

almost daily communication with Stanton, whose background was in government

propaganda.

Scaling Back

The day after Salant

informed CNEC about the proposed JFK assassination special, Salant told CBS

News vice president Manning that he was wavering on the mock trial concept.

Salant’s next move was even more ominous. He sent both Manning and prime-time

news producer Midgley to California to talk to two lawyers about the project.

One of the attorneys was Edwin Huddleson, a partner in

the San Francisco firm of Cooley, Godward, Castro and Huddleson. Huddleson

attended Harvard Law with Salant and, like Stanton, was on the board of the

Rand Corporation. The other lawyer was Bayless Manning, Dean of Stanford Law

School. They told the CBS representatives that they were against the network

undertaking the project on the grounds of “the national interest” and because

of the topic’s “political implications.”

CBS News vice president

Manning reported that both

attorneys advised the CBS team to ignore the critics of the Warren Commission

or to appoint a special panel to critique their books, in other words, to put

the critics on trial. Huddleson also steered the CBS team to cooperative

scientists who would counter the critics.

On his return to CBS

headquarters, Manning saw

the writing on the wall. He knew what his CBS superiors really wanted

and it wasn’t some no-holds-barred examination of the Warren Commission’s

flaws. So, he suggested a new title for the series, “In Defense of the Warren Report,” and

wrote that CBS should

dismiss “the inane, irresponsible, and hare-brained challenges of Mark Lane and

others of that stripe.”

Out on a Limb

Manning’s defection from

an open-minded treatment of the evidence to a one-sided Warren Commission

defense left producer Midgley out on a limb. However, unaware of what Salant

was up to, on Dec. 14, 1966, Midgley

circulated a memo about how he planned on approaching the Warren Report

project. He proposed running experiments that were more scientific than “the

ridiculous ones run by the FBI.” He still wanted a mock trial to show

how the operation of the Commission was “almost incredibly inadequate.”

In response, Salant circulated an anonymous, undated,

paragraph-by-paragraph rebuttal to Midgley’s plan, which Feinman’s later

investigation determined was written by Warren Commissioner John McCloy, then

Chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and the father of Ellen McCloy,

Salant’s administrative assistant.

John J. McCloy, one of the

Warren Commission members.

In this memo, McCloy wrote

that “the chief evidence that Oswald acted alone and shot alone is not to be

found in the ballistics and pathology of the assassination, but in the fact of his loner

life.” As many Warren Commission critics have noted, it was this

approach – discounting or

ignoring the medical and ballistics evidence, but concentrating on Oswald’s

alleged social life – that was a fatal flaw of the Warren Report.

Despite the familial

conflict of interest, Ellen McCloy was added to the distribution list for

almost all memos related to the Kennedy assassination project and thus could serve as a secret

back-channel between CBS and her father.

A Stonewall Defense

Clearly, the original idea

for a fresh examination of the Warren Commission and the evidence that had

arisen since its report was published in 1964 had been turned on its head. The CBS brass wanted a defense,

not a critique.

Salant asked producer Midgley, “Is the question whether

Oswald was a CIA or FBI informant really so substantial that we have to deal

with it?” Midgley, increasingly alone out on the limb, replied, “Yes, we must

treat it.”

As the initial plan for a

forthright examination of the Warren Commission’s shortcomings was transformed

into a stonewall defense of the official findings, there was still the problem

of Midgley, the last holdout. But eventually his head was turned, too.

While the four-night special was in production, Midgley

became engaged to Betty Furness, a former actress-turned-television-commercial

pitchwoman whom President Lyndon Johnson appointed as his special assistant for

consumer affairs, even though her

only experience in the field had been selling Westinghouse appliances for 11

years on television. She

was sworn in on April 27, 1967, which was about two months before the CBS

production aired. Two weeks after it was broadcast, Midgley and Furness were

married.

As Kai Bird’s biography of

McCloy, The Chairman,

makes clear, Johnson and McCloy were friends and colleagues. But there

is another point about how Midgley was convinced to go along with McCloy’s view

of the Warren Commission. Around the same time he married Furness, he received a significant

promotion, elevated to executive editor of the network’s flagship news program,

“The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.” This made him, in essence, the top

news editor at CBS, a decision that required the consultation and approval of

Salant, Cronkite and Stanton – and very likely the CNEC.

So, instead of a serious

investigation into the murder of President Kennedy – at a time when there was

the possibility of effective national action to get at the truth – CBS News

delivered a stalwart defense of the Warren Commission’s conclusions and heaped

ridicule on anyone who dared question those findings.

Shaping that approach was not only the influence of

Warren Commission member John McCloy, an icon of the Establishment, but the

carrots and sticks applied to senior CBS producers, such as Gordon Manning and

Les Midgley, who initially favored

a more skeptical approach but were convinced to abandon that goal.

Curious Consultants

Once McCloy was brought

onboard, the complexion of CBS’s treatment of the JFK assassination changed. CBS hired consultants who were

rabidly pro-Warren Report to appear as on-air experts while others would be

hidden in the shadows. In addition to the clandestine role of McCloy, some of

these consultants included Dallas police officer Gerald Hill, physicist Luis

Alvarez and reporter Lawrence Schiller.

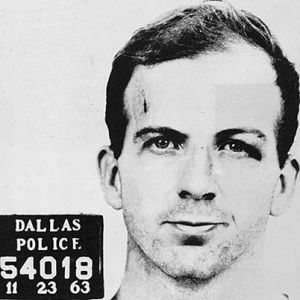

Lee Harvey Oswald, the

accused assassin of President John F. Kennedy.

Officer Hill was just about everywhere in Dallas on Nov.

22, 1963. He was at the Texas

School Book Depository where Oswald worked and allegedly shot the President

from the sixth floor; Hill was at the murder scene of Officer J. D Tippit, who

was allegedly shot by Oswald after he fled Dealey Plaza; and he was at the

Texas Theater where Oswald was arrested.

Hill appeared in the CBS

1967 program show as a speaker. But Roger Feinman found out that Hill also was

paid for six weeks work on the show as a consultant. During his consulting, Hill revealed that the police did a

“fast frisk” on Oswald while in the theater. They found nothing in his pockets

at the time, which begs the question of where the bullets the police said they

found in his pockets later at the station came from. That question did

not arise during the program since CBS never revealed the contradiction. (Click

here and go to page 20 of the transcript.)

Physicist Luis Alvarez, who had a served as an adviser to

the CIA and to the U.S. military in the Vietnam War, spent a considerable

amount of time lending his name to articles supporting the Warren Report and

conducting questionable experiments

supporting its findings. As demonstrated by authors Josiah Thompson (in 2013)

and Gary Aguilar (in 2014), Alvarez misrepresented some data in some of his JFK

experiments. (Click here and go to the 37:00 mark for Aguilar’s presentation.)

Making Fun

The same year of the 1967 CBS broadcast, reporter

Lawrence Schiller had co-written a book entitled The Scavengers and Critics of

the Warren Report, a picaresque

journey through America where Schiller interviewed some of the prominent – and

not so prominent – critics of the report and caricatured them hideously.

Secretly, he had been an informant for the FBI for many

years keeping an eye on people like Mark Lane and Jim Garrison, whom Schiller

attacked despite discovering witnesses who attested to Garrison’s suspect Clay

Shaw using the alias Clay Bertrand,

a key point in Garrison’s case. The relevant documents were not declassified

until the Assassination Records and Reviews Board was set up in the 1990s. [See

Destiny Betrayed, Second Edition, by James DiEugenio, p. 388]

This cast of consultants – along with McCloy – influenced the direction of the 1967 CBS Special

Report. The last thing these consultants wanted to do was to expose the faulty

methodology that the Warren Commission had employed.

Longtime CBS News anchor

Walter Cronkite.

As in 1964, Walter Cronkite manned the anchor desk and

Dan Rather was the main field reporter. Again, CBS could find no serious

problems with the Warren Report. The critics were misguided, CBS said. After

all, Cronkite and Rather had done a seven-month inquiry.

‘Unimpeachable

Credentials’

In the broadcast, Cronkite

names the men on the Warren Commission as their pictures appear on screen. He

calls them “men of

unimpeachable credentials” but left out the fact that President Kennedy

fired Commissioner Allen Dulles from the CIA in 1961 for lying to him about the

Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

When Cronkite got to the

crux of the program, he said the Warren Commission assured the American people

that they would get the most searching investigation in history. Then, Cronkite

showed books and articles critical of the commission and mentioned that polls

showed that a majority of Americans had lost faith in the Warren Report.

At that point, the network special revealed its purpose,

to discredit the critics and reassure the public that these people could not be

trusted.

Cronkite went through a

list of points that the critics had raised, including key issues such as how

many shots were fired and how quickly they could be discharged from the suspect

rifle. On each point,

Cronkite took the Warren Commission’s side, saying Oswald fired three shots

from the sixth floor with the rifle attributed to him by the Warren Commission.

Two of three were direct hits – to Kennedy’s head and shoulder area – within six

seconds.

One way that CBS fortified

the case for just three shots was Alvarez’s examination of the Zapruder film, Abraham Zapruder’s

26-second film of Kennedy’s assassination taken from Zapruder’s position in

Dealey Plaza, a sequence that CBS did not actually show.

Alvarez proclaimed that by

doing something called a “jiggle analysis,” he computed that there were three

shots fired during the film. What the jiggle amounted to was a blurring of

frames on the film (presumably because Zapruder would have flinched at the

sound of gunshots).

Dan Rather took this

Alvarez idea to Charles Wyckoff, a professional photo analyst in Massachusetts.

Agreeing with Alvarez, at least on camera, Wyckoff mapped out the three areas

of “jiggles.” The Alvarez/Wyckoff formula was simple: three jiggles, three

shots.

But as Feinman found out through his legal discovery and

hearings, there was a big problem with this declaration. Wyckoff had actually

discovered four jiggles, not three. Therefore, by the Alvarez formula, there

was a second gunman and thus a conspiracy.

President John F.

Kennedy's motorcade enters Dealey Plaza in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, shortly

before his assassination. (Zapruder film)

Wyckoff’s on-camera

discussion of this was cut out and not included in the official transcript. But

it is interesting to note just how committed Wyckoff was to the CBS agenda, for

he tried to explain the fourth jiggle as Zapruder’s reaction to a siren. As Feinman noted, how Wyckoff

could determine this from a silent 8 mm film is puzzling. But the point

is, this analysis did not support the commission. It undermined the Warren

Report and was left on the cutting-room floor.

There were other problems

with the Alverez-Wyckoff “jiggle” theory, since the first jiggle was at around Zapruder frame 190,

or a few frames previous to that, which would have meant that Oswald would have

had to be firing through the branches of an oak tree, which is why the

Warren Commission moved this shot up to frame 210.

But CBS left itself an

out, claiming there was an opening in

the tree branches at frame 186 and Oswald could have fired at that point. But

that is patently ridiculous, since the opening at frame 186 lasted for 1/18th of

a second. To say that Oswald anticipated a less than split-second opening, and

then steeled himself in a flash to align the target, aim, and fire is all stuff

from the realm of comic books super heroes. Yet, in its blind obeisance to the Warren Report, this is

what CBS had reduced itself to.

Another way that CBS tried

to bolster the Warren Report was to have Wyckoff purchase other Bell and Howell

movie cameras (since CBS was not allowed to handle the actual Zapruder camera.)

After winding up these cameras, CBS hypothesized that Zapruder’s camera might

have been running a little slow, giving Oswald a longer firing sequence.

The problem with this

theory, however, was that both the FBI and Bell and Howell had tested the speed

of Zapruder’s actual camera. Even

Dick Salant commented that this was “logically inconclusive and unpersuasive,”

but it stayed in the program.

The Shot Sequence

But why did Rather and Wyckoff have to stoop this low? The answer is because of the results of their rifle

firing tests. As the critics of the Warren Report had pointed out, the

commission had used two tests to see if Oswald could have gotten off three

shots in the allotted 5.6 seconds indicated by the Zapruder film.

These tests ended up as failing to prove Oswald could

have performed this feat of marksmanship. What made it worse is that the

commission had used very proficient rifleman to try and duplicate what the

commission said Oswald had done. [See Sylvia Meagher, Accessories After the

Fact, p. 108]

So CBS tried again. This

time they set up a track with a sled on it to simulate the back of Kennedy’s

head. They then elevated a firing point to simulate the sixth floor “sniper’s

nest,” though there were differences from Dealey Plaza including the oak tree

and a rise in the street in the real crime scene. Nevertheless, the CBS

experimenters released the target on its sled and had a marksman named Ed

Crossman fire his three shots.

Crossman had a

considerable reputation in the field, but – even though he was given a week to

practice with a version of the Mannlicher Carcano rifle – his results were not

up to snuff. According to

a report by producer Midgley, Crossman never broke 6.25 seconds (longer than

Oswald’s purported 5.6 seconds) and – even with an enlarged target – he got only

two of three hits in about 50 percent of his attempts.

Crossman explained that

the rifle had a sticky bolt action and a faulty viewing scope. But what the professional sniper

did not know is that the actual rifle in evidence was even harder to work.

Crossman said that to perform such a feat on the first time out would require a

lot of luck.

The Mannlicher-Carcano

rifle allegedly used to murder President John F. Kennedy.

However, since that

evidence did not fit the show’s agenda, it was discarded, both the test and the

comments. To resolve that problem, CBS called in 11 professional marksmen who first went to an indoor

firing range and practiced to their heart’s content, though the Warren

Commission could find no evidence that Oswald practiced.

The 11 men then took 37

runs at duplicating what Oswald was supposed to have done. There were three

instances where two out of three hits were recorded in 5.6 seconds. The best

time was achieved by Howard Donahue on his third attempt after his first two

attempts were complete failures.

But CBS claimed that the average recorded time was 5.6

seconds, without including the 17 attempts that were thrown out because of

mechanical failure. CBS also didn’t tell the public the surviving average was

1.2 hits out of three with an enlarged target.

The truly striking

characteristic of these trials was the amount of instances where the shooter

could not get any result at all. More often than not, once the clip was loaded, the bolt action jammed.

The sniper had to realign the target and fire again. According to the

Warren Report, that could not have happened with Oswald.

There is also the anomaly

of James Tague, who was struck by one bullet that the Warren Commission said

had ricocheted off the curb of a different street, about 260 feet away from the

limousine. But how could Oswald have missed by that much if he was so accurate

on his other two shots? That was another discrepancy deleted by the CBS

editors.

The Autopsy Disputes

CBS also obscured what was

said by the two chief medical witnesses after the assassination by Dr. Malcolm

Perry from Parkland Hospital in Dallas, where Kennedy was taken after he was

hit, and James Humes, the chief pathologist at the autopsy examination at

Bethesda Medical Center that evening.

In their research for the series, CBS had discovered a

transcript of Dr. Perry’s press conference that the Warren Commission did not

have. But CBS camouflaged what Perry said on Nov. 22, 1963, specifically about

Kennedy’s anterior neck wound. Perry said it had the appearance to him of being

an entrance wound, and he said this three times.

Cronkite tried to

characterize the conference as Perry being rushed out to the press and

badgered. But that wasn’t

true, since the press conference was about two hours after Perry had done a

tracheotomy over the front neck wound. The performance of that incision

had given Perry the closest and most deliberate look at that wound.

Perry therefore had the

time to recover from the pressure of the operation and there was no badgering

of Perry. Newsmen were simply asking him questions about the wounds he saw.

Perry had the opportunity to answer the questions on his own terms. Again, CBS seemed intent on

concealing evidence of a possible second assassin — because Oswald could

not have fired at Kennedy from the front.

Commander James Humes, the pathologist, did not want to

appear on the program, but was pressured by Attorney General Ramsey Clark,

possibly with McCloy’s assistance.

As Feinman discovered, the preliminary talks with Humes were done through a

friend of his at the church he attended.

There were two things that

Humes said in these early discussions that were bracing. First, he said that he

recalled an x-ray of the President, which showed a malleable probe connecting

the rear back wound with the front neck wound. Second, he said that he had

orders not to do a complete autopsy. He would not reveal who gave him these orders, except to say that it

was not Robert Kennedy. [Charles Crenshaw, Trauma Room One, p. 182]

The significance of the

malleable probe is that, if Humes was correct, the front and back wounds would

have come from the same bullet. However, we learned almost 30 years later from

the Assassination Records Review Board that other witnesses also saw a malleable probe go through

Kennedy’s back, but said the probe did not go through the body since the wounds

did not connect. However, x-rays that might confirm the presence of the probe

are missing. [DiEugenio, Reclaiming Parkland, pgs. 116-18]

Location of the Wounds

On camera, Humes also said

the posterior body wound was at the base of the neck. Dan Rather then showed

Humes the drawings made of the wound in the back as depicted by medical

illustrator Harold Rydberg for the Warren Commission, also depicting the wound

as being in the neck, which Humes agreed with on camera. He added that they had

reviewed the photos and referred to measurements and this all indicated the

wound was in the neck.

Even for CBS — and Warren Commissioner John McCloy — this

must have been surprising since the autopsy photos do not reveal the wound to

be at the base of the neck but clearly in the back. (Click here and scroll

down.) CBS should have sent its own independent expert to the archive because

Humes clearly had a vested interest in seeing his autopsy report bolstered, especially

since it was under attack by more than one critic.

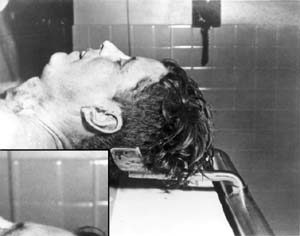

Autopsy photo of President

John F. Kennedy.

The second point that

makes Humes’s interview curious is his comments on the Rydberg drawings’

accuracy. These do not coincide with what Rydberg said later, not understanding

why he was chosen to make these drawings for the Warren Commission since he was

only 22 and had been drawing for only one year. There were many other veteran

illustrators in the area the Warren Commission could have called upon, but Rydberg came to believe that

it was his inexperience that caused the commission to pick him.

When Humes and Dr.

Thornton Boswell appeared before him, they had nothing with them: no photos, no

x-rays, no official measurements, speaking only from memory, nearly four months

after the autopsy, Rydberg said. [DiEugenio, Reclaiming Parkland, pgs. 119-22] The Rydberg drawings have become

infamous for not corresponding to the pictures, measurements, or the Zapruder

film.

For Humes to endorse these on national television – and

for CBS to allow this without any fact-checking – shows what a case of false

journalism the special had become.

Limiting Access

CBS also knew that Humes

said he had been limited in what he was allowed to do in the Kennedy autopsy, a

potentially big scoop if CBS had followed it. Instead, the public had to wait another two years for the

story to surface at Garrison’s trial of Clay Shaw when autopsy doctor Pierre

Finck took the stand in Shaw’s defense. Finck said the same thing: that Dr.

Humes was limited in his autopsy practice on Kennedy. [ibid, p. 115]

The difference was that

this disclosure would have had much more exposure, impact and vibrancy if CBS

had broken it in 1967 rather than having the fact come up during Garrison’s

prosecution, in part, because the press corps’ hostility toward Garrison

distorted the trial coverage.

So, in the summer of 1967, CBS again had come to the

defense of the official story with a four-hour, four-night extravaganza that

again endorsed the findings of the Warren Commission.

At the time of broadcast, it was the most expensive

documentary CBS ever produced. It concluded: Acting alone, Lee Harvey Oswald

killed President Kennedy. Acting alone, Jack Ruby killed Oswald. And Oswald and

Ruby did not know each other. All the controversy was Much Ado about Nothing.

Unwinding the Back Story

In 1967, the clandestine relationship between CBS News

President Salant and Warren Commissioner McCloy was known to very few people.

In fact, as assistant producer Roger Feinman later deduced, it was likely known only to the very small circle in

the memo distribution chain. That Salant deliberately wished to keep it hidden

is indicated by the fact that

he allowed McCloy to write these early memos anonymously.

As Feinman concluded,

McCloy’s influence over the program was almost certainly a violation of the

network’s own guidelines, which

prohibit conflicts of interest in the news production, probably another reason

Salant kept McCloy’s connection hidden.

In the 1970s, after

Feinman was fired over a later dispute regarding another example of CBS News’

highhanded handling of the JFK assassination – and then obtained internal

documents as part of a legal hearing on his dismissal – he briefly thought of

publicizing the whole affair (which he eventually decided against doing).

But Feinman wrote to

Warren Commissioner McCloy in March 1977 about the ex-commissioner’s

clandestine role in the four-night special a decade earlier. McCloy declined to

be interviewed on the subject, but added that he did not recall any

contribution he made to the special.

But Feinman persisted. On April 4, 1977, he wrote McCloy

again. This time he revealed that he had written evidence that McCloy had

participated extensively in the production of the four-night series. Very

quickly, McCloy got in contact with Salant and wrote that he did not recall any

such back-channel relationship.

In turn, Salant contacted

Midgley and told the producer to check his files to see if there was any

evidence that would reveal a CBS secret collaboration with McCloy. Salant then wrote back to McCloy

saying that at no time did Ellen McCloy ever act as a conduit between CBS News

and her father.

However, in 1992 in an

article for The Village Voice, both Ellen McCloy and Salant were confronted

with memos that revealed Salant was lying in 1977. McCloy’s daughter admitted to the clandestine

courier relationship. Salant finally admitted it also, but he tried to

say there was nothing unusual about it. [See

http://www.assassinationresearch.com/v1n2/mediaassassination.html]

Reassuring Americans

So, in 1967, CBS News had

again reassured the American people that there was no conspiracy in President

Kennedy’s murder, just a misguided lone gunman who had done it all by himself.

Anyone who thought otherwise was confused, deceptive or delusional.

However, in 1975, eight

years after the broadcast, two events revived interest in the JFK case again. First, the Church Committee was

formed in Congress to explore the crimes of the CIA and FBI, revealing that

before Kennedy was killed, the CIA had farmed out the assassination of Fidel

Castro to the Mafia, a fact that was kept from the Warren Commission

even though one of its members, Allen Dulles, had been CIA director when the

plots were formulated.

Longtime CBS anchor Dan

Rather

Secondly, in the summer of 1975, in prime time,

ABC broadcast the Zapruder film, the first time that the American public had

seen the shocking image of President Kennedy’s head being knocked back and to

the left by what appeared to be a shot from his front and right, a shot Oswald

could not have fired.

The confluence of these

two events caused a furor in Washington and the creation of the House Select

Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) to reopen the JFK case.

Having become a chief

defender of the original Warren Commission findings, CBS News moved preemptively to influence the new

investigation by planning another special about the JFK case.

CBS’s Sixty Minutes

decided to do a story on whether or not Jack Ruby and Lee Oswald knew each

other. After several months of research, Salant killed the project with the investigative files

turned over to senior producer Les Midgley before becoming the basis for

the 1975 CBS special, which was entitled The American Assassins.

Originally this was

planned as a four-night special. One night each on the JFK, RFK, Martin Luther

King and the George Wallace shootings. But at the last moment, in a very late

press release, CBS announced that the first two nights would be devoted to the

JFK case. Midgley was the

producer, but this time Cronkite was absent. Rather took his place behind the

desk.

In general terms, it was more of the same. The photographic consultant was Itek Corporation, a

company that was very close to the CIA, having helped build the CORONA spy

satellite system. Itek’s CEO in the mid-1960s, Franklin Lindsay, was a former

CIA officer. With Itek’s

help, CBS did everything they could to move their Magic Bullet shot from about

frame 190 to about frames 223-226.

Yet, Josiah Thompson, who

appeared on the show, had written there was no evidence Gov. Connally was hit

before frames 230-236. Further,

there are indications that President Kennedy is clearly hit as he disappears

behind the Stemmons Freeway sign at about frame 190, e.g., his head seems to

collapse both sideways and forward in a buckling motion.

But with Itek in hand,

this became the scenario for the CBS version of the “single bullet theory.” It

differed from the Warren Commission’s in that it did not rely upon a “delayed

reaction” on Connally’s part to the same bullet.

Ballistics Tests

CBS also employed Alfred Olivier, a

research veterinarian who worked for Army wound ballistics branch and did tests

with the alleged rifle used in the assassination. He was a chief witness for junior counsel Arlen Specter

before the Warren Commission. [See Warren Commission, Volume V, pgs.

74ff]

For CBS in 1975, Olivier

said that the Magic Bullet, CE 399, was not actually “pristine.” For CBS and

Dan Rather, this made the “single bullet theory” not impossible, just hard to

believe.

Apparently, no one

explained to Rather that the only

deformation on the bullet is a slight flattening at the base, which would occur

as the bullet is blasted through the barrel of a rifle. There is no deformation at its

tip where it would have struck its multiple targets. There is only a tiny amount of

mass missing from the bullet.

In other words, as more

than one author has written, it has all the indications of being fired into a

carton of water or a bale of cotton. If CBS had interviewed the legendary

medical examiner Milton Helpern of New York — not far from CBS headquarters —

that is pretty much what he would have said. [Henry Hurt, Reasonable Doubt, p.

69.]

Rather realized, without

being explicit, that something was wrong with Kennedy’s autopsy. He called the

autopsy below par and reversed field on his opinion about pathologist Humes,

whose experience Rather had praised in 1967. In the 1975 broadcast, Rather said

that neither Humes nor Boswell were qualified to perform Kennedy’s autopsy and

that parts of it were botched.

But let us make no mistake

about what CBS was up to here. The

entire corporate upper structure — Salant, Stanton, Paley — had overrun the

working producers and journalists, including Midgley, Manning and Schorr. And

those subordinates decided not to utter a peep to the outside world about what

had happened.

Not only Cronkite and Rather participated in this

appalling exercise, so too did Eric Sevareid, appearing at the end of the last

show and saying that there are always those who believe in conspiracies,

whether it be about Yalta, China or Pearl Harbor. He then poured it on by

saying some people still think Hitler is alive and concluding that it would be

impossible to cover up the assassination of a President.

But simply in examining

how a major news outlet like CBS handled the evidence shows precisely how

something as dreadful and significant as the murder of a President could be

covered up.

Much of this history also

would have remained

unknown, except that Roger Feinman, an assistant producer at CBS News, had become

a friend and follower of the estimable Warren Commission critic Sylvia Meagher.

So, Feinman knew that the Warren Commission was a deeply flawed report and that

CBS had employed some very questionable methods in the 1967 special in order to

conceal those flaws.

When the assassination

issue returned in the mid-1970s, Feinman began to write some memoranda to those

in charge of the renewed CBS investigation warning that they shouldn’t repeat

their 1967 performance. His

first memo went to CBS president Dick Salant. Many of the other memos were

directed to the Office of Standards and Practices.

In preparing these memos,

Feinman researched some of the odd methodologies that CBS used in 1967. Since

he had been at CBS for three years, he got to know some of the people who had

worked on that series. They supplied him with documents and information which

revealed that what Cronkite and Rather were telling the audience had been

arrived at through a process that was as flawed as the one the Warren

Commission had used.

Feinman requested a formal

review of the process by which CBS had arrived at its forensic conclusions. He

felt the documentary had violated company guidelines in doing so.

Establishment Strikes Back

As Feinman’s memos began to circulate through the

executive and management suites – including Salant’s and Vice-President Bill

Small’s – it was made clear to him

that he should cease and desist from his one-man campaign. When he wouldn’t let

up, CBS moved to terminate its

dissident employee.

Roger Feinman

But since Feinman was

working under a union contract, he had certain administrative rights to a fair

hearing, including the process of discovery through which he could request

certain documents to make his case. His research allowed him to pinpoint where

these documents would be and who prepared them.

On Sept. 7, 1976, CBS

succeeded in terminating Feinman. But the collection of documents he secured through his hearing was

extraordinary, allowing outsiders for the first time to see how the 1967 series

was conceived and executed. Further, the documents took us into the

group psychology of a large media corporation when it collides with

controversial matters involving national security.

Only Roger Feinman, who was not at the top of CBS or anywhere near it, had

the guts to try to get to the bottom of the whole internal scandal.

And Feinman paid a high

personal price for doing so. Feinman’s contribution to American history did not

help him get his journalistic career back on track. When he passed away in the fall of 2011, he was

freelancing as a computer programmer.

[This article is largely based on the script for the

documentary film Roger Feinman was in the process of reediting at the time of his

death in 2011. The reader can view that here.]

James DiEugenio is a

researcher and writer on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and

other mysteries of that era. His most recent book is Reclaiming Parkland.

FOREIGN POLICY, INTELLIGENCE, LOST HISTORY, MEDIA, POLITICS, SECRECY